Investigators still don’t know who killed Arthur Langley. The 62-year-old San Diego man was found shortly before midnight last June, in his car, in the middle of 45th Street near a Southcrest park. He’d been shot.

Four hours later, police knocked on his sister’s door.

“Totally devastating,” Kathleen Medina said. “I just don’t know who did it — or why.”

Langley’s unsolved shooting happened in a year in which — while COVID kept people indoors and under tremendous stress — homicides in San Diego County jumped by 35 percent.

Two years ago, 85 people died by homicide in the region, according to the Union-Tribune’s analysis of data collected from local law enforcement agencies. Last year, there were 115 reported homicides.

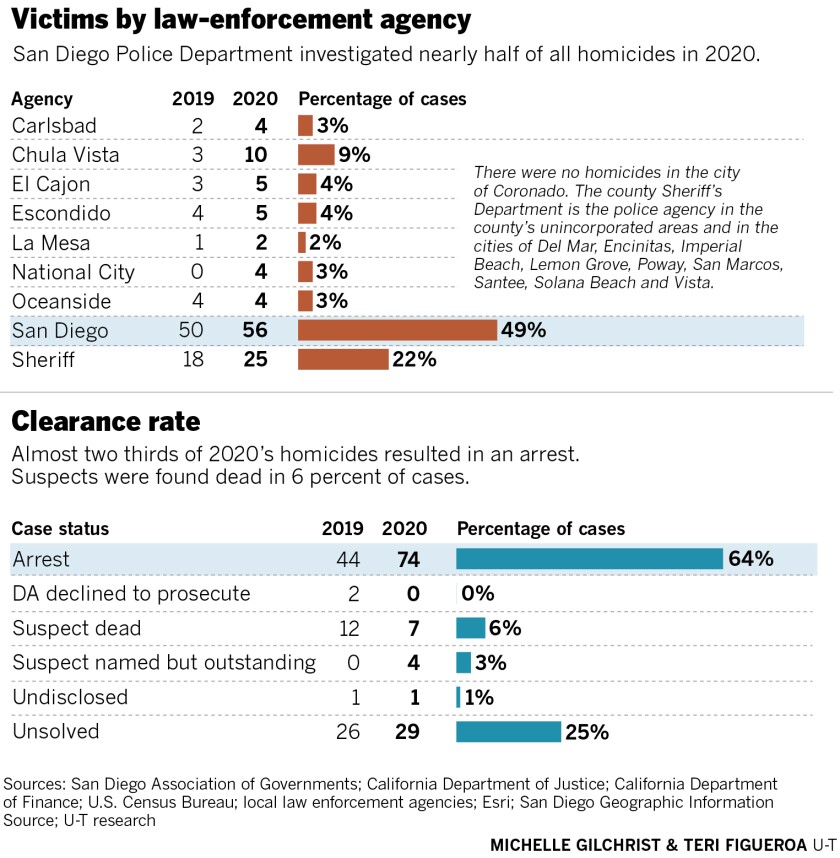

Homicides more than tripled in Chula Vista, rising from three killings to 10. National City went from no homicides to four. The city of San Diego, with 56 reported homicides last year, had a more than 10 percent hike.

The Union-Tribune gathers data on homicides in the region each year, a review that shows possible trends as well a sense of who the victims were and how they died.

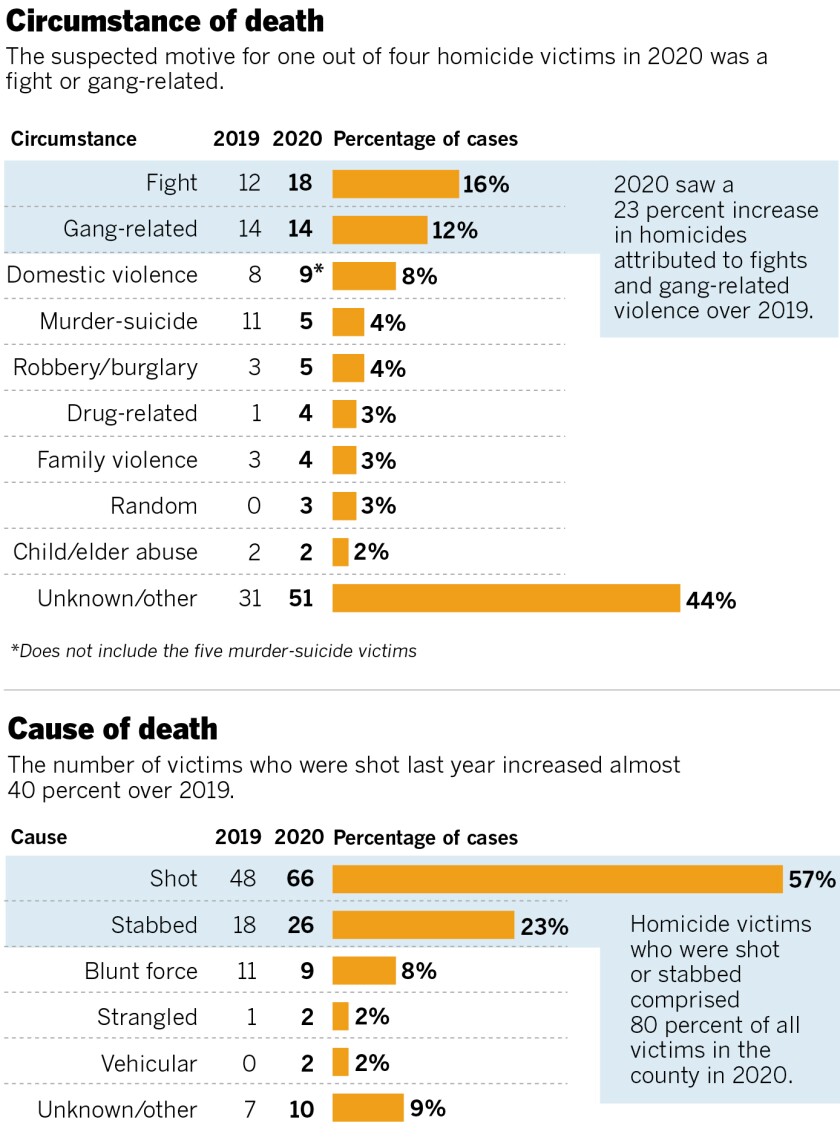

In San Diego County last year, guns were far and away the weapon most often used in killings, involved in nearly three of every five slayings. In the city of San Diego, two of every three killings involved a gun.

San Diego police say they are finding far more guns, including in the hands of felons, and more untraceable “ghost guns,” which are assembled from parts that sometimes come in prepackaged kits. They are often unregistered and untraceable.

Last year, San Diego, like the rest of the country, wrestled with increasing gun violence. Assaults involving guns were up, and more people are calling 911 to report hearing gunfire. And twice last year, alerts from ShotSpotter, a network of audio sensors said to detect gunfire, led San Diego police to discover the scenes of deadly shootings that no one had called to report.

Gun deaths have accounted for 55 to 57 percent of the region’s killings each year since 2018. The year before that, half the homicides involved guns. In 2016, it was 40 percent.

Recent rise in numbers

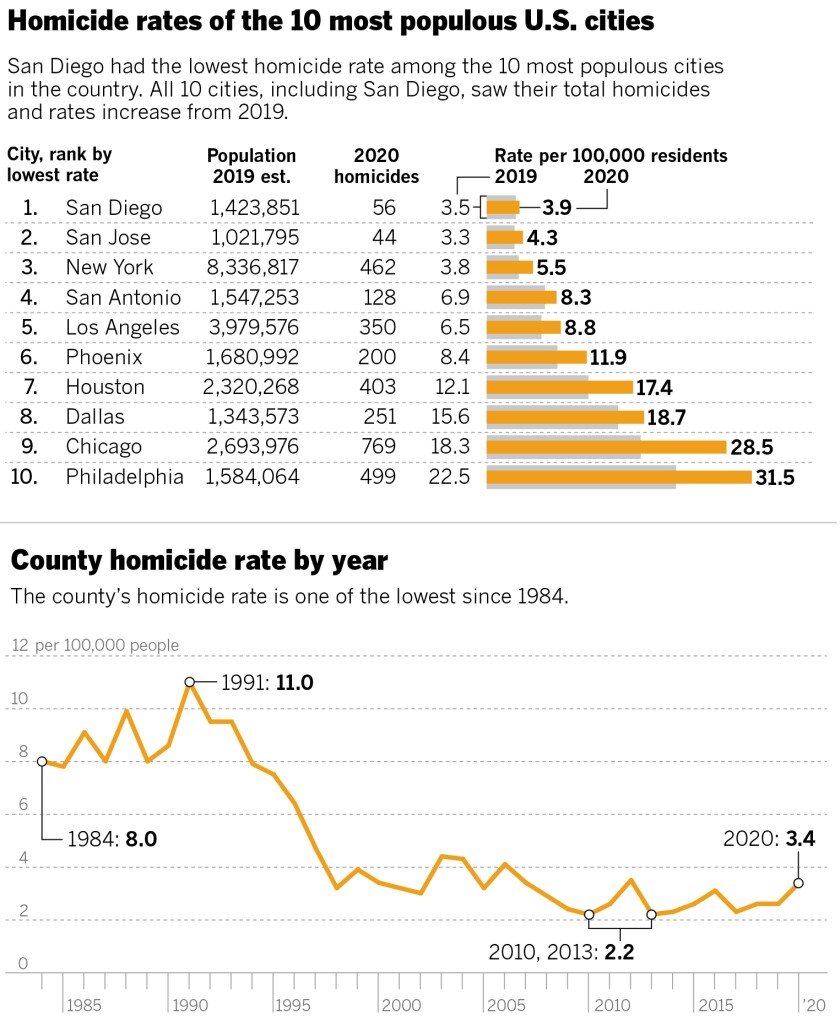

San Diego, the eighth largest city in the United States, is not alone in the spike in killings. Nationwide, several big cities saw huge jumps in homicides from 2019 to 2020 — Chicago vaulted from 495 to 769, Houston rose from 288 to 403, and Los Angeles went from 258 to 350.

Looking solely at homicides, San Diego is the safest of the 10 most populous American cities, with a ratio of 3.9 homicides per 100,000 residents. (Two years ago, it was 2.5 per 100,000.)

San Antonio, with about 100,000 more residents than San Diego, had a ratio of 8.3, with 128 slayings designated as homicides last year to San Diego’s 56. Dallas, with a slightly smaller population, had 251 homicides. The ratio was 18.7 deaths per 100,000 residents.

Despite the recent uptick, violent crime generally has been trending downward nationally and locally for decades. Thirty years ago, San Diego County peaked at a record 278 homicides, and the city tallied 167.

In 2010, the city of San Diego dipped to 29 homicides — a low not seen since 1968. The following years brought fluctuations, but San Diego logged 34 homicides in 2017, and 35 the following year.

The city recorded 50 homicides in 2019. Ten of those deaths happened in just three incidents.

Among them: a Paradise Hills mother and her four young sons, all shot to death by the boys’ father, who then turned the gun on himself. There was a Logan Heights house fire that killed a couple and one of their daughters — a fire that one of the couple’s sons is accused of intentionally starting. And a Torrey Highlands couple was shot and killed by their son, who jumped to his death from University City freeway overpass.

Last year, the city of San Diego had only one incident with multiple fatalities — a double homicide, the shooting deaths of the mother and grandmother of an infant boy. That means 51 separate incidents of killings in 2020.

Data collected by The San Diego Union-Tribune includes incidents that happened in prior years but were not designated as homicides until later. Last year, four San Diego police cases fell into that category, including three that were relatively recent. The fourth was the April death of a San Diego police officer who was on the job when he was shot and paralyzed in 2003.

The ‘why’ remains elusive

Police can’t say why the numbers are up.

“I don’t know that I have a reason,” Chula Vista police Capt. Eric Thunberg said. “I think we have to consider that COVID played a role, because homicides and violent crimes went up everywhere.”

“A lot of this will have to be studied by researchers after the fact.”

Thunberg said he has found that killings are often crimes of passion, “spontaneous events of emotions that are hard to predict.”

“Sometimes people don’t think about their actions, they just react,” he said.

Lt. Tom Seiver oversees the homicide unit at the county Sheriff’s Department, and he said homicide is unique and often personal. There are usually “varied reasons and motivations in any crime.” It’s difficult to pinpoint one, he said.

The Sheriff’s Department is contracted to handle law enforcement in several cities from Vista to Santee to Imperial Beach as well as in unincorporated areas. The number of homicides it investigated rose from 18 to 25 — a nearly 39 percent increase.

Fatal stabbings accounted for nearly a quarter of the killings last year. Blunt force — generally, beating a person to death — happened about 8 percent of the time. Two people were strangled.

There were five-murder-suicides in the county last year, according to data provided by law enforcement agencies. In 2019, there were 11.

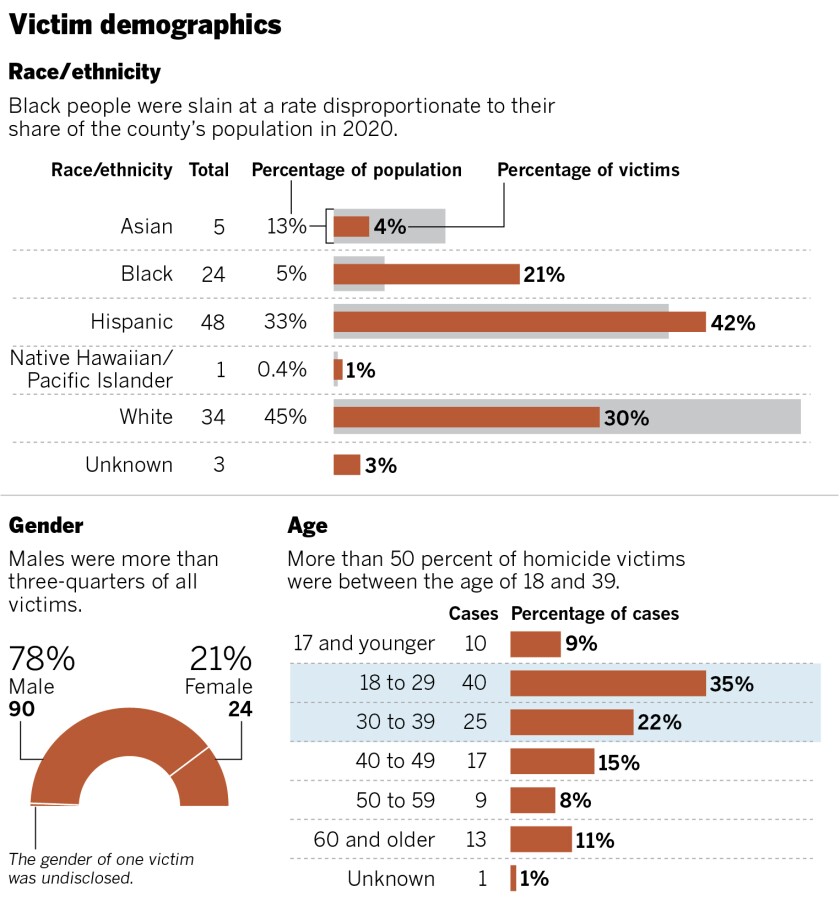

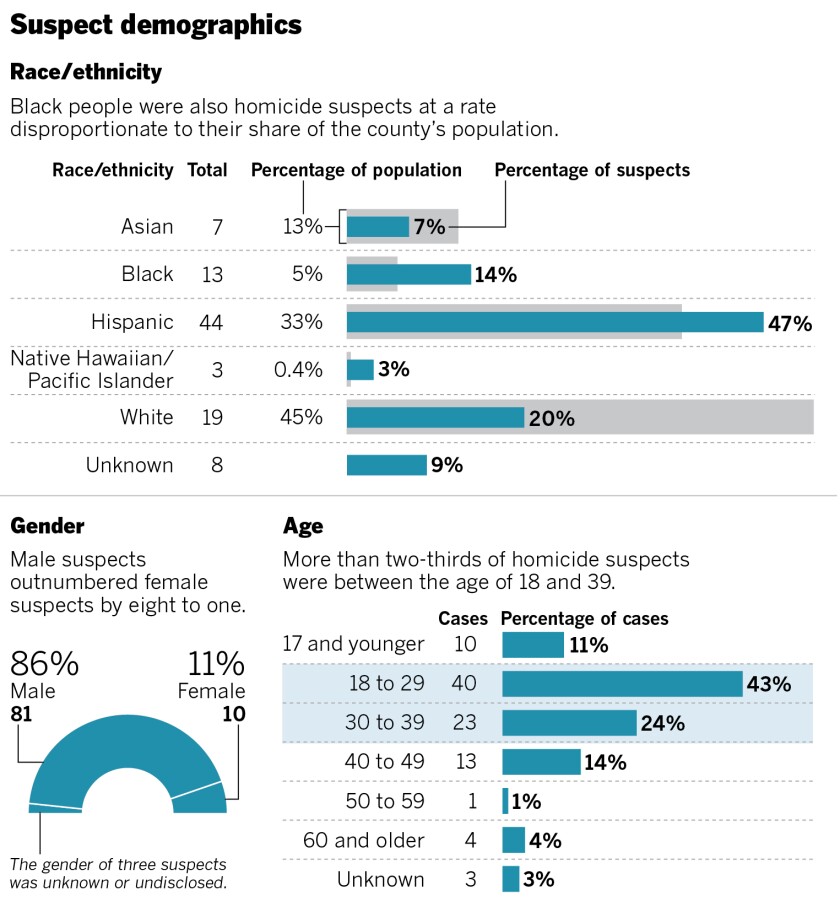

In four out of every five killings in the region last year, the victim was a man. Six of ten victims were Black or Latino. More than two-thirds of the time, the victim was between the ages of 18 to 39.

A quarter of the killings across the county last year are unsolved, but that doesn’t mean investigators don’t have a suspect. They just might not have enough to make an arrest.

Sometimes, police won’t say what may have motivated a killing. Sometimes they say they don’t know.

San Diego saw a jump in gang killings in recent years. A few years ago, the number of suspected gang-related deaths in the city was two. Last year, it was 11. The year before that, it was 12. That’s roughly 20 percent of the city’s killings.

A focus on stopping gun violence

Earlier this year, the city introduced a pilot program to quell rising gang violence. Dubbed “No Shots Fired,” it calls for outreach and wraparound support services for gang members. It starts with getting gang members to agree to a cease-fire period, creating accountability and deploying services they might need. The focus is on stopping gun violence.

“We are in a state of emergency when it comes to gun violence, and we need to treat it like an epidemic,” said Bishop Cornelius Bowser, who works on gang violence prevention and intervention. He said he initiated the program in San Diego.

He spoke of the need to intervene in the hours after a shooting, and noted that COVID lockdowns limited valuable in-person talks — which start when the victim is still in the hospital — to quash retaliation. In all aspects, he said, COVID-19 played a deleterious role.

“Violence was already rising, then the pandemic came and it opened the top and caused it to escalate,” he said.

Bowser said there are lots of guns on the streets — “You’d be surprised at the amount,” he said — including ghost guns.

San Diego police spokesman Shawn Takeuchi said police investigations into shootings went up at the start of year, and calls from people who reported hearing gunfire jumped 70 percent. In the first two months of 2020, 361 people picked up the phone to do so. Those same months this year: 617 calls.

The number of felons in San Diego arrested for possessing a guns spiked 75 percent from 2019 to 2020. Under state law, felons are barred from possessing guns and ammunition.

San Diego police impounded 210 ghost guns last year, close to triple what they found the previous year. And as of the first week April, San Diego police had already seized 111 ghost guns — more than half of what they collected all of last year.

‘My brother didn’t deserve it’

Police are still investigating Langley’s death, and his sister continues to grapple with it. He was the baby of the family, the youngest of 11.

He had once been a certified nurse’s assistant, Medina said, and had taken care his mother until she died. After that, Langley moved in with Medina.

He mostly stayed home, watching cowboy movies, she said. And he loved to fish. On the night of his death, he’d spent time visiting with another of his sisters. He never made it home.

“He wasn’t the kind of person to bother anybody,” Medina said. “My brother didn’t deserve it.”